From rainfall to resilience: Engineers Without Borders ensures clean water for Amazonian Village

There's no lack of rain in Libertad, Peru, but there is a shortage of clean, usable water.

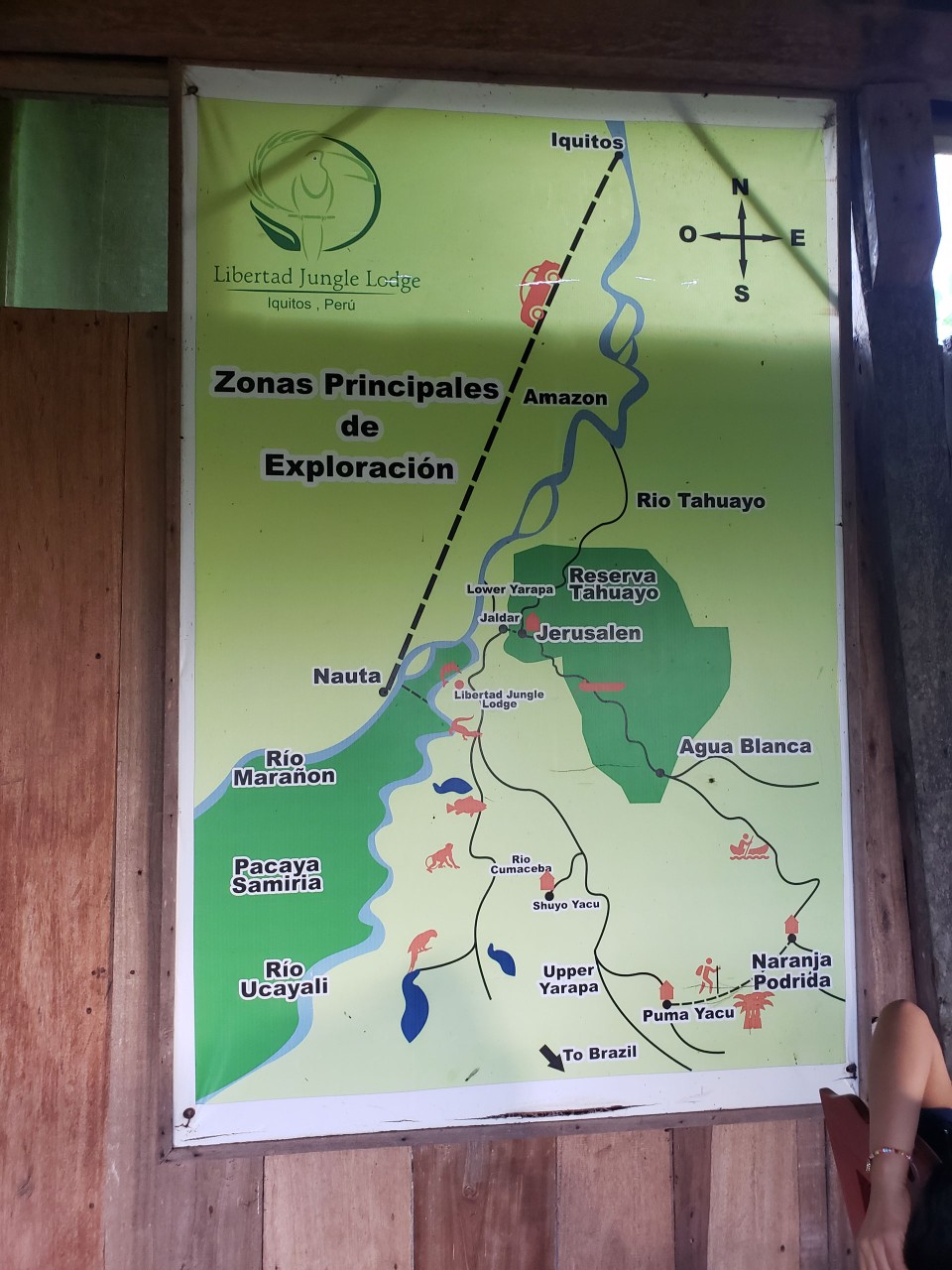

This Village, deep in the Peruvian Amazon Rainforest, is home to monkeys, iguanas, piranhas and native Peruvians whose ancestors once lived on these lush riverbanks. This region gets 112 inches of rain every year, so much so that it even rains daily during the dry season. By comparison, the Midwest tends to get 35 to 40 inches of rain each year.

And yet, the Amazon rainwater is easily polluted.

On a tributary of the Amazon River, Libertad frequently floods and river water mixes with sewage. The groundwater well, installed by the Peruvian government, is used for laundry and washing but is not safe to drink.

There's no trip to Walmart for a case of bottled water in Libertad. The nearest city is a two-hour boat ride away. To prevent illness and disease caused by contaminated water, volunteers from Engineers Without Borders (EWB) began working with villagers to create a rainwater catchment system.

Designed to capture and filter rainwater so it can be safely used, these systems can be long-term solutions for people living in the Amazon. That's why when I got the opportunity to travel to this South American country, I took it.

The community in Libertad had a rainwater catchment system designed by EWB volunteers, including my twin sister, Nicole. It used a first-flush system, which directs the initial runoff away from the system. There also is a mesh to prevent leaves, mosquitos and debris from entering the piping, and water goes through chlorination before use.

That system had to be installed remotely during the COVID-19 pandemic and completed by 2023. The wooden base was rotting, there was coliform in the water, and the quantity of rainwater collected was not sufficient. That brought EWB volunteers to Libertad to install a second system.

During a prior visit, other EWB volunteers worked on a concrete foundation and columns for the second catchment system. Our team's task was to complete a concrete platform and connect tanks via pipes to gutters that catch the rainwater.

I started the week in the Amazon by helping local workers level the concrete form needed for the platform. Then, our team worked to caulk gutters and rivet their ends together. The gutters collect rainwater and deliver it to tanks for filtration.

Upon testing, however, it was evident the water wasn't being effectively chlorinated. Our team looked deeper into the problem and realized the edges of the chlorine tablet, which was being cut into quarters prior to use, were still jagged – an indication that the water wasn't flowing over and dissolving it. We theorized that the bag holding the tablet was floating, with water never getting inside it to the chlorine. We pushed the bag further into the pipe to force water through it in hopes of boosting chlorination.

Our team also found that the mosquito netting at the end of the overflow pipes had been left open for a period, and there were gaps where the piping met the tank. Those issues allowed newts to enter, contributing to the positive coliform test, so our team sealed the gap.

With water quality improving, construction continued on the catchment system. Tanks were installed and wooden stairs, painted with a tar-based substance to prevent termites, were built to access the platform.

There still is work to do. Once villagers finish the construction of their building, they will need to install more gutters and pipes. EWB might help.

During the trip, my group also spent time in a classroom, where we taught local children the importance of handwashing to stay healthy. We also discussed safe methods of collecting and treating rainwater to avoid cross-contamination.

The volunteer group also met with community leaders in charge of water for Libertad. We shared the chlorine bag trick, discussed a funding plan for future maintenance and reviewed the catchment system's operation manual. It was in Spanish and came with pictograms, that I was able to illustrate for villagers who couldn't read.

The experience of meeting people from a new culture while getting to do hands-on construction is one I won't forget. I brought back to Fehr Graham a greater ability to develop ingenious solutions in scenarios that might not be ideal.

And, of course, I'll have the satisfaction of knowing that somewhere in the Peruvian Amazon, a small Village is drinking clean and healthy water.

|

Kelsey Bird is an Environmental Engineer who works to remove environmental hazards to improve public health. Whether she’s completing an Environmental Site Assessment or groundwater sampling or performing due diligence – her work helps communities thrive. She is a skilled researcher and data tabulator. Kelsey is an expert in technical reporting and is part of a team that works toward sustainable recreational facilities. Reach her at |

Collaborative, Insightful, Results-Driven Solutions

Fehr Graham provides innovative engineering and environmental solutions to help improve the lives and communities of our customers.